Ten years ago, the “make or buy” question often boiled down to a simple calculation: do we have the developers to build it? Today, with agentic AI accelerating development and standardizing practices, the equation deserves to be revisited.

Not that the answer has become simpler. It’s still “it depends.” But the criteria on which it depends have evolved.

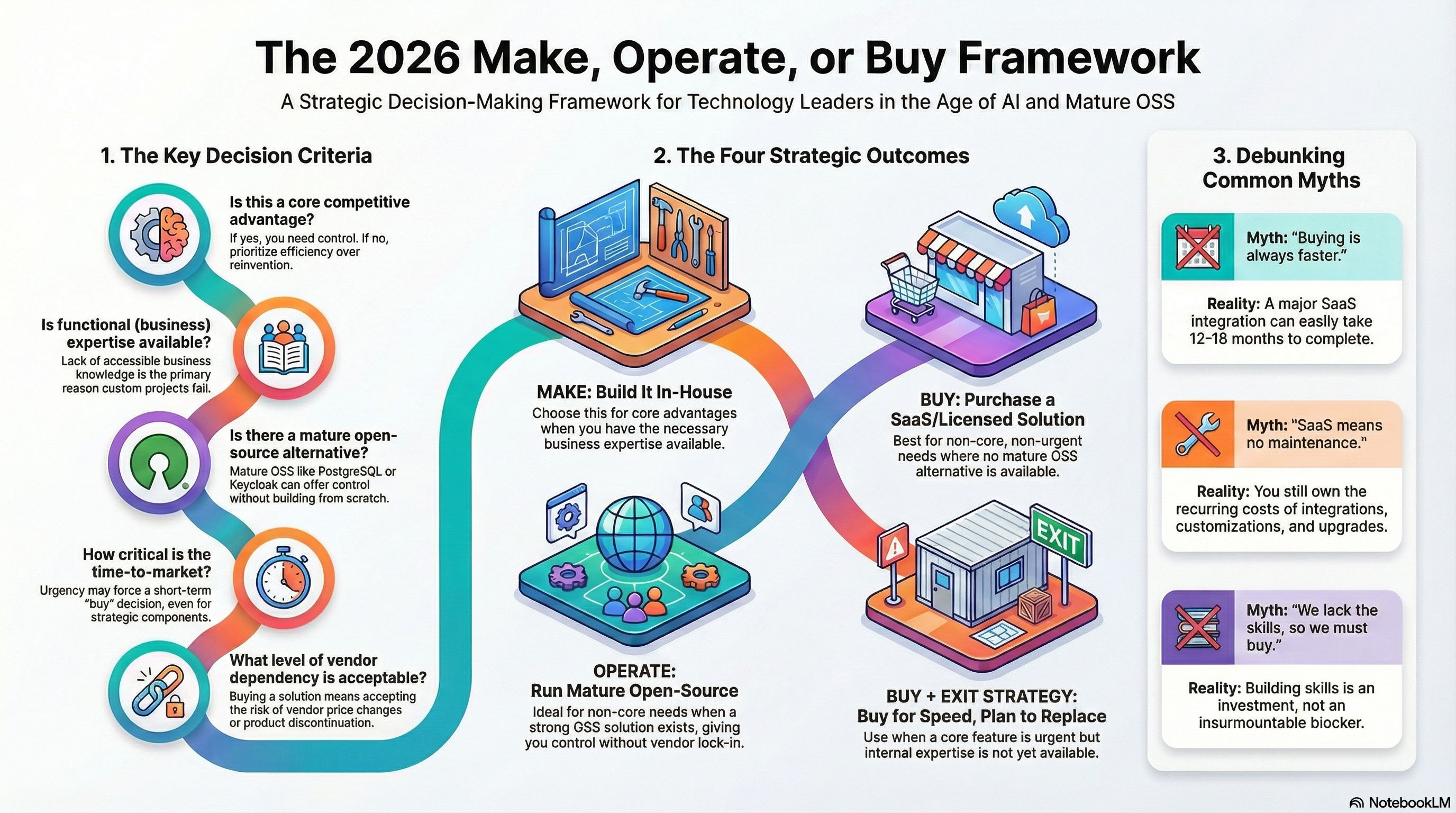

Overview of the decision framework

The Myths That Lead to Bad Decisions

Let’s start by clearing out the reflexes that lead to dead ends — on both sides.

The Buy Side

Warning

Myth: “Buying is faster.”

That’s rarely true. A Salesforce or SAP integration takes 12 to 18 months in the best case. Add the “essential” customizations, data migrations, and change management. Meanwhile, a well-structured internal team could have delivered a targeted, operational tool.

Warning

Myth: “SaaS means no maintenance.”

SaaS shifts maintenance, it doesn’t eliminate it. Integrations with your information system, specific workflows, business-requested changes — all of that remains your responsibility. And when the vendor decides to deprecate a feature you’re using, that’s your problem.

The Make Side

Warning

Myth: “We don’t have the skills, so we can’t.”

That’s confusing a current state with a fate. Skills can be built: recruitment, training, external support. The question isn’t “can we do it?” but “how much does it cost to learn how, and is it worth it?”

Warning

Myth: “We can build it in two weeks.”

The POC-becomes-product syndrome. Yes, you can prototype quickly. But software in production also means edge case handling, documentation, support, updates, and security. Two weeks become six months, then two years of maintenance.

Warning

Myth: “If we didn’t code it, it’s not good.”

The NIH syndrome — Not Invented Here. Recoding an authentication system, a workflow engine, or a message bus because you want to “master” it… is often wasted energy. Open source projects like Keycloak have years of head start and hundreds of contributors. Except in exceptional cases, you don’t recode Keycloak.

The Real Question: Where Is Your Competitive Advantage?

Before talking technology, budget, or timeline, there’s a question to settle: does what we’re building differentiate us in the market?

This is the fundamental dividing line.

What falls under “core” — where your competitive advantage lies — deserves investment to master it. Using the same tools as everyone else means, at best, being at market level. To do better, you need tools that reflect your specificities.

What falls under “commodity” — what everyone does the same way — doesn’t justify reinventing the wheel. Payroll, leave management, authentication: except in very specific cases, that’s not where you’ll make a difference.

A Concrete Example

Take two retail players. The first built its advantage on sourcing: finding the right products, the right suppliers, before others. The second bets everything on supply chain execution: delivering faster, cheaper, with fewer errors.

For the first, the purchasing management and supplier relationship system is strategic. It’s worth building something specific.

For the second, it’s the logistics management tool that deserves the investment. The rest can be standardized.

Tip

The Spectrum of Options

Make or Buy is a false dilemma. In reality, you have a continuum of options, each with its balance between control and burden.

The Make Side

Pure internal make. Your teams design and develop. You control everything: the code, the architecture, the roadmap. It’s maximum control — and maximum responsibility. You bear the full cost: development, maintenance, updates, support.

Make with contractors. You have specific software built by a services company or freelancers, but you remain the owner. The code is yours, the technical debt too. You outsource execution, not responsibility.

Make on open source foundation. You start from an existing base — a framework, a technical building block — and build on top. You benefit from the community’s work for foundations, you invest in what differentiates you.

The Operate Side

This is the third way, often forgotten in the debate.

Open source operated internally. You deploy a mature solution — Keycloak, Kafka, PostgreSQL — and maintain it. No license, no vendor lock-in. In exchange, you must build the competency to operate it: monitoring, updates, security, scaling.

Managed open source. You use the same building block, but a third party operates it for you. RedHat for Keycloak, Confluent for Kafka, your cloud provider for managed PostgreSQL. You pay to avoid carrying the operational burden, while maintaining relative independence from a proprietary vendor.

The Buy Side

License + integration. You buy a software component and build around it. It’s the historical model: an ERP, a CRM, a WMS that you install and integrate into your IS. You have access to the product, you can customize it, but you depend on the vendor for updates and support.

Customizable vendor solution. On-premise, private cloud, or extensible SaaS. The vendor provides a platform you adapt to your needs. More flexibility than pure SaaS, but also more integration work. And always the question: what happens if the vendor changes strategy?

Pure SaaS. You take the product as is. You adapt to its constraints, its workflows, its data model. It’s minimum burden — and minimum control. If the product doesn’t do what you want, you have two options: change your process or change products.

The Slider

It’s not a question of better or worse. It’s a slider.

The more you go toward pure Make, the more control you have over your destiny. You decide everything. But you carry everything: costs, risks, complexity.

The more you go toward pure SaaS, the less burden you have daily. Someone else manages infrastructure, updates, security. But you’re a tenant, not an owner. Your room for maneuver depends on the vendor’s goodwill.

The challenge is positioning the slider in the right place for each need. And that right place depends on a simple criterion: is this need at the heart of your competitive advantage?

The Criteria That Really Matter

Functional Expertise: The Real Bottleneck

We often talk about technical skills. Rarely about the real limiting factor: business expertise.

You can have the best development team on the market. If the business isn’t available to specify, challenge, validate — your Make will produce a tool that misses the mark. And no agentic AI compensates for absent business knowledge.

Info

Two questions to ask:

- Does functional expertise exist internally?

- Is it actually available?

The second point is often underestimated. Expertise that exists but is only available 30 minutes every 6 months is almost worse than no expertise at all. You think you have it, you launch the project, and you discover too late that no one is there to arbitrate.

Note: this criterion also applies to Buy. Without business availability, your SaaS integration will drift the same way. But SaaS at least has a “default path” that limits damage.

The Third Way: Open Source

The Make or Buy debate often obscures an intermediate option: operating an open source solution.

Keycloak for IAM. Kubernetes for orchestration. PostgreSQL for databases. These projects have reached such maturity that they’ve become de facto standards.

Operating open source is neither Make nor Buy. You don’t start from zero, but you keep control. No multi-million dollar licenses, no vendor lock-in, and a community that evolves the product.

The cost? The ability to operate. Which brings us to the next criterion.

Budget and Sovereignty

Having budget isn’t “buying for buying’s sake.” It’s giving yourself choice.

The more financial room you have, the more you can decide your level of dependency on a vendor. Building a team capable of operating Keycloak rather than signing with Okta for several hundred thousand euros per year is an investment in sovereignty.

Conversely, a constrained budget sometimes forces painful trade-offs. You buy because you don’t have the means to build internal capacity. It’s not a bad choice — it’s a constrained choice that must be assumed as such.

Danger

The real risk: the dependency blind spot.

Real case: a retailer whose central supply chain component relied on a vendor. Hundreds of thousands of euros invested in integration and customization. One day, the vendor announces they’re discontinuing the product. Good luck.

Time — On Both Sides

“We don’t have time, so we buy.”

That’s often a dangerous shortcut. Time plays on both sides.

A SaaS or vendor integration never happens painlessly. Count 12 to 18 months for a major project, with no guarantee of success. Meanwhile, an internal team with the right functional expertise can deliver a targeted first version in a few months.

Where time becomes truly critical is in situations of strategic urgency. A competitor investing in your market, an opportunity to seize quickly. In that case, the question becomes: what gives me a competitive advantage fastest?

If functional expertise is available: targeted Make, fast.

If it isn’t: Buy to go fast, but with a control recovery strategy. You’re buying time, not a definitive solution.

The Decision Grid

Here are the questions to ask, in order.

1. Is it a competitive advantage?

If yes, mastery matters. Lean toward Make or Operate. If not, no need to reinvent the wheel — Buy or managed OSS may suffice.

2. Is functional expertise available?

Not “does it exist somewhere in the company.” Is it available, now, for this project? If yes, Make becomes viable. If not, either invest to make it available, or go with Buy with a default path that limits damage.

3. Is there a mature open source solution?

For IAM, orchestration, databases, messaging — the answer is often yes. In that case, the question becomes: operate internally or go managed? The choice depends on your ability to build and maintain that competency.

4. What’s the strategic urgency?

If you have time, you can build the capacity you’re missing. If a competitor is investing in your market tomorrow, you may not have that luxury. In that case, buy time — but with a control recovery strategy.

5. What’s your real budget?

Not the project budget. The budget that includes 5-year maintenance, updates, hidden costs. And above all: do you have the budget to choose, or are you constrained to endure?

6. What level of dependency do you accept?

This is the sovereignty question. A vendor can change prices, deprecate a feature, discontinue a product. Are you ready to carry that risk? Do you have a plan B?

In Summary

| Criterion | Leans toward Make/Operate | Leans toward Buy |

|---|---|---|

| Competitive advantage | Yes | No |

| Functional expertise available | Yes | No or weak |

| Mature OSS available | Operate | Buy if no OSS |

| Strategic urgency | Make if expertise available | Buy + exit strategy |

| Sufficient budget | Freedom of choice | Constrained choice |

| Dependency tolerance | Low → Make/Operate | Acceptable → Buy |

This isn’t an algorithm. It’s a reading grid to structure discussion and challenge reflexes.

Conclusion

The answer is always “it depends.” But now you know on what.

Agentic AI changes the equation — not just because we code faster, but because we can standardize practices, share blueprints, industrialize what was artisanal. Make has never been so accessible.

That said, it’s not a reason to rebuild everything. The real work is identifying what truly differentiates you. Honestly assessing whether business expertise is there — and available. Evaluating your tolerance for dependency. Owning your choices, even when they’re constrained.

A CIO who has worked through these questions can defend their strategy before any board. Not with certainties, but with a method. And when facing a technology choice, that’s often the only thing that matters.

Comments

💬 Comments are shared across all language versions of this article.